Introduction

AI remains the only powerful technology lacking meaningful binding safety standards. This is not for lack of risks. The rapid development and deployment of ever-more powerful systems is now absorbing more investment than that of any other models. Along with great benefits and promise, we are already witnessing widespread harms such as mass disinformation, deep- fakes and bias – all on track to worsen at the currently unchecked, unregulated and frantic pace of development. As AI systems get more sophisticated, they could further destabilize labor markets and political institutions, and continue to concentrate enormous power in the hands of a small number of unelected corporations. They could threaten national security by facilitating the inexpensive development of chemical, biological, and cyber weapons by non-state groups. And they could pursue goals, either human- or self-assigned, in ways that place negligible value on human rights, human safety, or, in the most harrowing scenarios, human existence.

Despite acknowledging these risks, AI companies have been unwilling or unable to slow down. There is an urgent need for lawmakers to step in to protect people, safeguard innovation, and help ensure that AI is developed and deployed for the benefit of everyone. This is common practice with other technologies. Requiring tech companies to demonstrate compliance with safety standards enforced by e.g. the FDA, FAA or NRC keeps food, drugs, airplanes and nuclear reactors safe, and ensures sustainable innovation. Society can enjoy these technologies’ benefits while avoiding their harms. Why wouldn’t we want the same with AI?

With this in mind, the Future of Life Institute (FLI) has undertaken a comparison of AI governance proposals, and put forward a safety framework which looks to combine effective regulatory measures with specific safety standards.

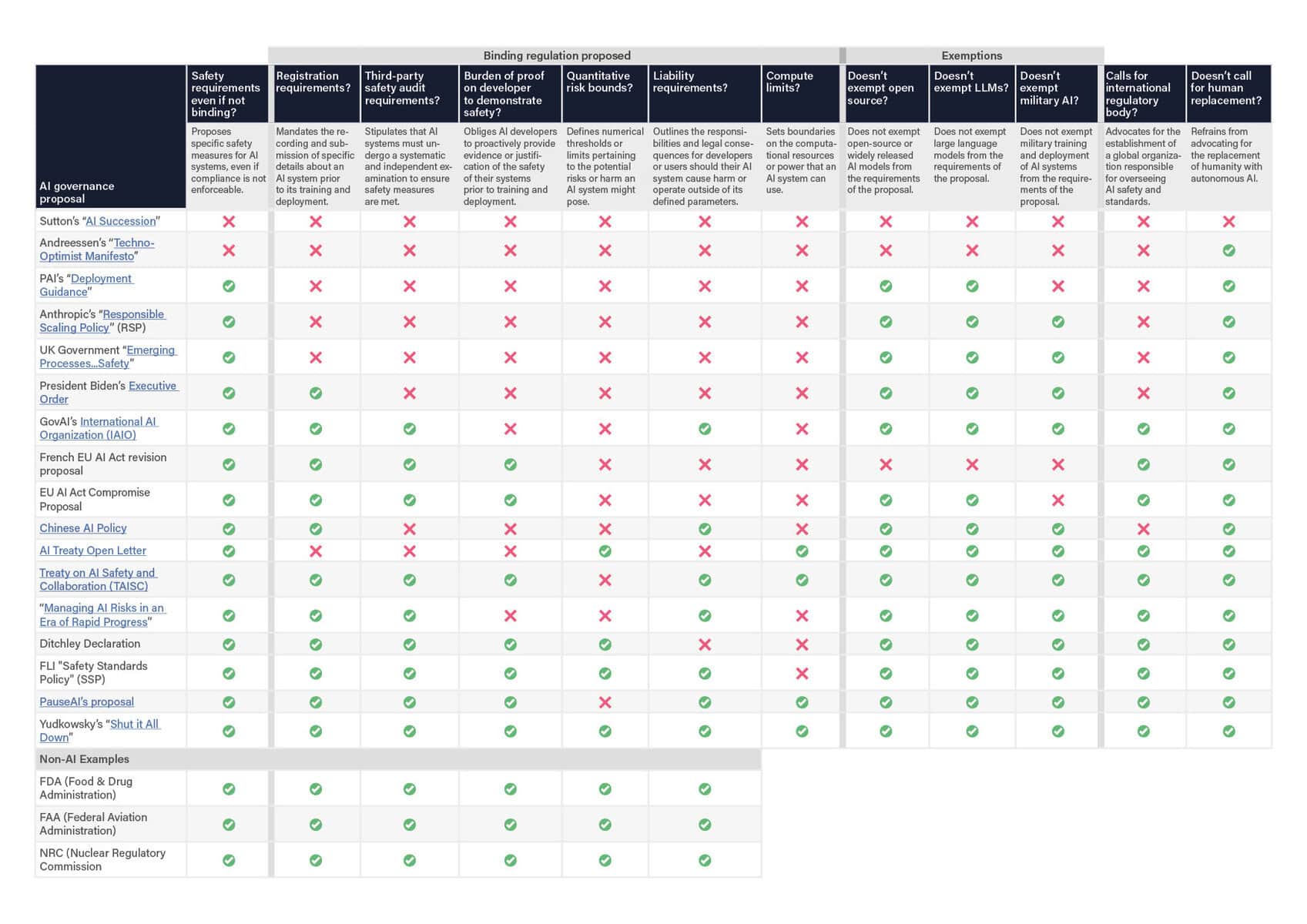

AI Governance Scorecard

Recent months have seen a wide range of AI governance proposals. FLI has analyzed the different proposals side-by-side, evaluating them in terms of the different measures required. The results can be found below. The comparison demonstrates key differences between proposals, but, just as importantly, the consensus around necessary safety requirements. The scorecard focuses particularly on concrete and enforceable requirements, because strong competitive pressures suggest that voluntary guidelines will be insufficient.

The policies fall into two main categories: those with binding safety standards (akin to the situation in e.g. the food, biotech, aviation, automotive and nuclear industries) and those without (focusing on industry self-regulations or voluntary guidelines). For example, Anthropic’s Responsible Scaling Policy (RSP) and FLI’s Safety Standards Policy (SSP) are directly comparable in that they both build on four AI Safety Levels – but where FLI advocates for an immediate pause on AI not currently meeting the safety standards below, Anthropic’s RSP allows development to continue as long as companies consider it safe. The FLI SSP is seen to check many of the same boxes as various competing proposals that insist on binding standards, and can thus be viewed as a more detailed and specific variant alongside Anthropic’s RSP.

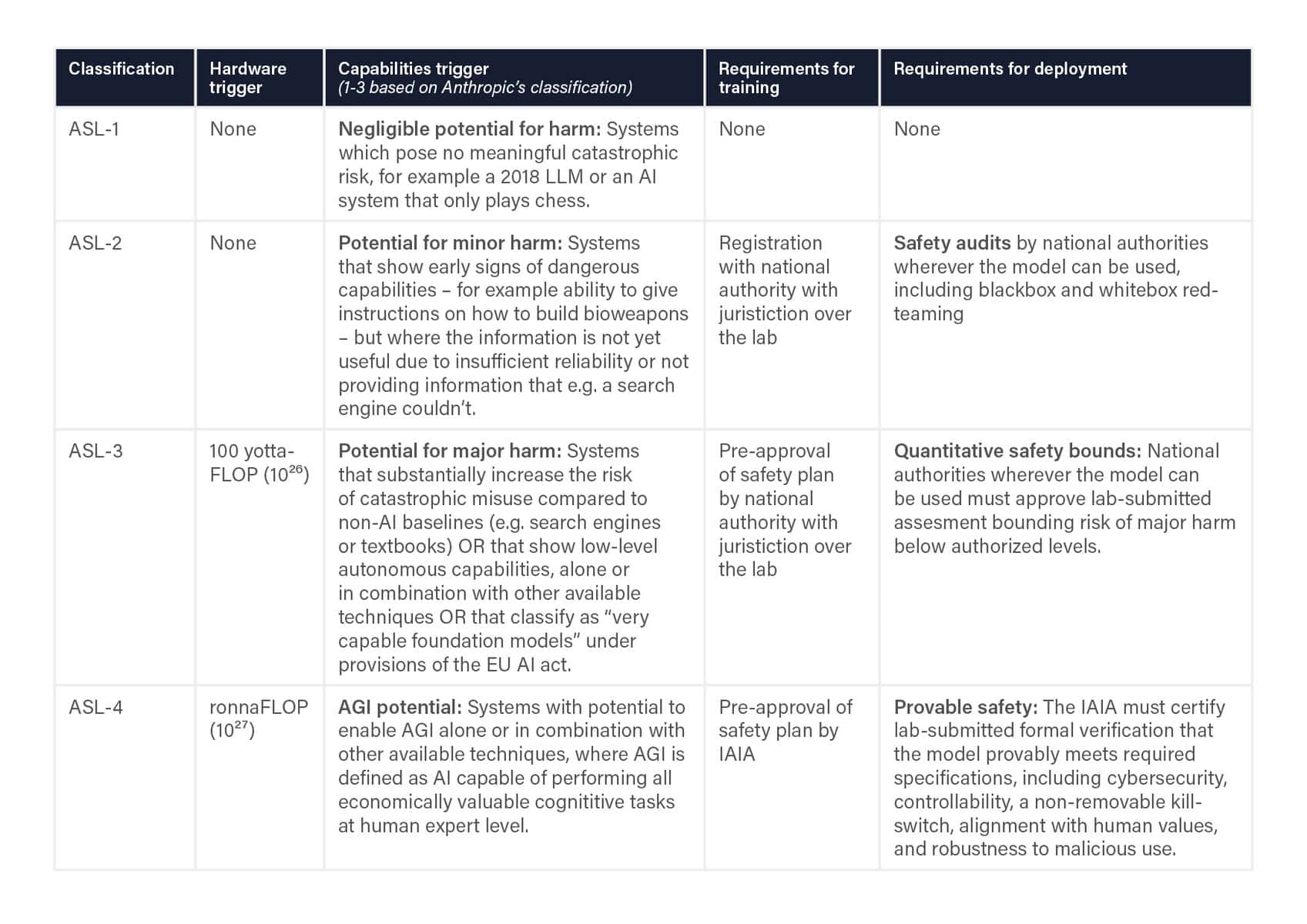

FLI Safety Standards Policy (SSP)

Taking this evaluation and our own previous policy recommendations into account, FLI has outlined an AI safety framework that incorporates the necessary standards, oversight and enforcement to mitigate risks, prevent harms, and safeguard innovation. It seeks to combine the “hard-law” regulatory measures necessary to ensure compliance – and therefore safety – with the technical criteria necessary for practical, real-world implementation.

The framework contains specific technical criteria to distinguish different safety levels. Each of these calls for a specific set of hard requirements before training and deploying such systems, enforced by national or international governing bodies. While these are being enacted, FLI advocates for an immediate pause on all AI systems that do not meet the outlined safety standards.

Crucially, this framework differs from those put forward by AI companies (such as Anthropic’s ‘Responsible Scaling Policy’ proposal) as well as those organized by other bodies such as the Partnership on AI and the UK Task Force, by calling for legally binding requirements – as opposed to relying on corporate self-regulation or voluntary commitments.

The framework is by no means exhaustive, and will require more specification. After all, the project of AI governance is complex and perennial. Nonetheless, implementing this framework, which largely reflects a broader consensus among AI policy experts, will serve as a strong foundation.

Table 2: FLI’s Proposed Policy Framework. View as a PDF.

Clarifications

Triggers: A given ASL-classification is triggered if either the hardware trigger or the capabilities trigger applies.

Registration: This includes both training plans (data, model and compute specifications) and subsequent incident reporting. National authorities decide what information to share.

Safety audits: This includes both cybersecurity (preventing unauthorized model access) and model safety, using whitebox and blackbox evaluations (with/without access to system internals).

Responsibility: Safety approvals are broadly modeled on the FDA approach, where the onus is on AI labs to demonstrate to government-appointed experts that they meet the safety requirements.

IAIA international coordination: Once key players have national AI regulatory bodies, they should aim to coordinate and harmonize regulation via an international regulatory body, which could be modeled on the IAEA – above this is referred to as the IAIA (“International AI Agency”) without making assumptions about its actual name. In the interim before the IAIA is constituted, ASL-4 systems require UN Security Council approval.

Liability: Developers of systems above ASL-1 are liable for harm to which their models or derivatives contribute, either directly or indirectly (via e.g. API use, open-sourcing, weight leaks or weight hacks).

Kill-switches: Systems above ASL-3 need to include non-removable kill-switches that allow appropriate authorities to safely terminate them and any copies.

Risk quantification: Quantitative risk bounds are broadly modeled on the practice in e.g. aircraft safety, nuclear safety and medicine safety, with quantitative analysis producing probabilities for various harms occurring. A security mindset is adopted, whereby the probability of harm factors in the possibility of adversarial attacks.

Compute triggers: These can be updated by the IAIA, e.g. lowered in response to algorithmic improvements.

Why regulate now?

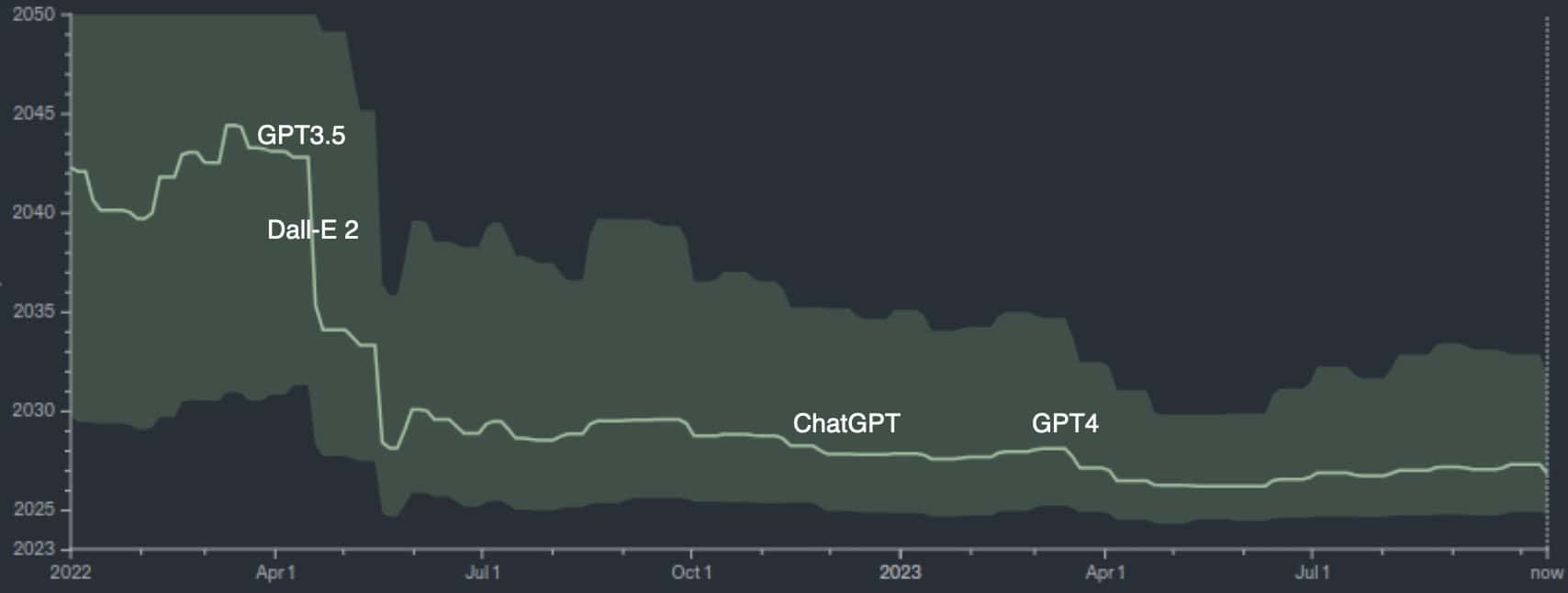

Until recently, most AI experts expected truly transformative AI impact to be at least decades away, and viewed associated risks as “long-term”. However, recent AI breakthroughs have dramatically shortened timelines, making it necessary to consider these risks now. The plot below (courtesy of the Metaculus prediction site) shows that the number of years remaining until (their definition of) Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) is reached has plummeted from twenty years to three in the last eighteen months, and many leading experts concur.

Image: ‘When will the first weakly general AI system be devised, tested, and publicly announced?‘ at Metaculus.com

For example, Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei predicted AGI in 2-3 years, with 10-25% chance of an ultimately catastrophic outcome. AGI risks range from exacerbating all the aforementioned immediate threats, to major human disempowerment and even extinction – an extreme outcome warned about by industry leaders (e.g. the CEOs of OpenAI, Google DeepMind & Anthropic), academic AI pioneers (e.g. Geoffrey Hinton & Yoshua Bengio) and leading policymakers (e.g. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak).

Reducing risks while reaping rewards

Returning to our comparison of AI governance proposals, our analysis revealed a clear split between those that do, and those that don’t, consider AGI-related risk. To see this more clearly, it is convenient to split AI development crudely into two categories: commercial AI and AGI pursuit. By commercial AI, we mean all uses of AI that are currently commercially valuable (e.g. improved medical diagnostics, self-driving cars, industrial robots, art generation and productivity-boosting large language models), be they for-profit or open-source. By AGI pursuit, we mean the quest to build AGI and ultimately superintelligence that could render humans economically obsolete. Although building such systems is the stated goal of OpenAI, Google DeepMind, and Anthropic, the CEOs of all three companies have acknowledged the grave associated risks and the need to proceed with caution.

The AI benefits that most people are excited about come from commercial AI, and don’t require AGI pursuit. AGI pursuit is covered by ASL-4 in the FLI SSP, and motivates the compute limits in many proposals: the common theme is for society to enjoy the benefits of commercial AI without recklessly rushing to build more and more powerful systems in a manner that carries significant risk for little immediate gain. In other words, we can have our cake and eat it too. We can have a long and amazing future with this remarkable technology. So let’s not pause AI. Instead, let’s stop training ever-larger models until they meet reasonable safety standards.

The argument for applying AI Act obligations only at the end of the value chain is that regulation will propagate back. If an EU small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) has to meet safety standards under the EU AI Act, they will only want to buy general-purpose AI systems (GPAIS) from companies that provide enough information and guarantees to assure them that the final product will be safe. Currently, however, our research demonstrates that general-purpose AI developers do not voluntarily provide such assurance to their clients.

We have examined the Terms of Use of major GPAIS developers and found that they fail to provide downstream deployers with any legally enforceable assurances about the quality, reliability, and accuracy of their products or services.

Table 1: Mapping Terms of Use conditions from major general-purpose AI developers which would apply to downstream companies.

This table may not display properly on mobile. Please view on a desktop device.

| OpenAI Terms of Use | Meta AIs Terms of Service | Google API Terms, Terms of Service | Anthropic Terms of Service | Inflection AI Terms of Service | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Services are provided “as is”, meaning the user agrees to receive the product or service in its present condition, faults included – even those not immediately apparent. | ✔️ | ✔️ | ✔️ | ✔️ | ✔️ |

| Warranties, including those of quality, reliability, or accuracy, are disclaimed. | ✔️ | ✔️ | ✔️ | ✔️ | ✔️ |

| The developer is not liable for most types of damages, including indirect, consequential, special, and exemplary damages. | ✔️ | ✔️ | ✔️ | ✔️ | ✔️ |

| Liability is limited to $200 (or less) or the price paid by the buyer. | ✔️ | ✔️ | ✔️ | ✔️ | |

| The developer is indemnified against claims arising from the user’s use of their models, only if the user has breached the developer’s terms. | ✔️ | ✔️ | ✔️ | ✔️ | |

| The developer is indemnified against claims arising from the user’s content or data as used with the developer’s APIs. | ✔️ | ✔️ | |||

| The developer is indemnified against any claims arising from the use of their models. | ✔️ |

Note: In some jurisdictions, consumer protection laws are strong and will prohibit the disclaimer of implied warranties or certain types of damages, but this is less likely for business-to-business transactions.

All five companies examined have strict clauses disclaiming any warranties about their products (both express and implied) and stating that their products are provided “as is”. This means that the buyer is accepting the product in its current state, with any potential defects or issues, and without any guarantee of its performance.

Furthermore, all five GPAIS developers inserted clauses into their terms stating that they would not be liable for most types of damages. For example, OpenAI states that they will not be liable “for any indirect, incidental, special, consequential or exemplary damages … even if [OpenAI has] been advised of the possibility of such damages”. In any case, they all limit their liability to a maximum of $200, or whatever the business paid for their products or services.

In fact, many even include indemnity1 clauses, meaning that under certain circumstances the downstream deployer will have to compensate the GPAIS developer for certain liabilities if a claim is brought against them. Anthropic, which has the most far-reaching indemnity clause, requires that businesses accessing their models through APIs indemnify them against essentially any claim related to that access, even if the business did not breach Anthropic’s Terms of Service.

Given the asymmetry of power between GPAIS developers and downstream deployers who tend to be SMEs, the latter will probably lack the negotiating power to alter these contractual terms. As a result, these clauses place an insurmountable due diligence burden on companies who are likely unaware of the level of risk they are taking on by using these GPAIS products.

This open letter is also available as a PDF.

Dear Senate Majority Leader Schumer, Senator Mike Rounds, Senator Martin Heinrich, Senator Todd Young, Representative Anna Eshoo, Representative Michael McCaul, Representative Don Beyer, and Representative Jay Obernolte,

As two leading organizations dedicated to building an AI future that supports human flourishing, Encode Justice and the Future of Life Institute represent an intergenerational coalition of advocates, researchers, and technologists. We acknowledge that without decisive action, AI may continue to pose civilization-changing threats to our society, economy, and democracy.

At present, we find ourselves face-to-face with tangible, wide-reaching challenges from AI like algorithmic bias, disinformation, democratic erosion, and labor displacement. We simultaneously stand on the brink of even larger-scale risks from increasingly powerful systems: early reports indicate that GPT-4 can be jailbroken to generate bomb-making instructions, and that AI intended for drug discovery can be repurposed to design tens of thousands of lethal chemical weapons in just hours. If AI surpasses human capabilities at most tasks, we may struggle to control it altogether, with potentially existential consequences. We must act fast.

With Congress slated to consider sweeping AI legislation, lawmakers are increasingly looking to experts to advise on the most pressing concerns raised by AI and the proper policies to address them. Fortunately, AI governance is not zero-sum – effectively regulating AI now can meaningfully limit present harms and ethical concerns, while mitigating the most significant safety risks that the future may hold. We must reject the false choice between addressing the documented harms of today and the potentially catastrophic threats of tomorrow.

Encode Justice and the Future of Life Institute stand in firm support of a tiered federal licensing regime, similar to that proposed jointly by Sen. Blumenthal (D-CT) and Sen. Hawley (R-MO), to measure and minimize the full spectrum of risks AI poses to individuals, communities, society, and humanity. Such a regime must be precisely scoped, encompassing general-purpose AI and high-risk use cases of narrow AI, and should apply the strictest scrutiny to the most capable models that pose the greatest risk. It should include independent evaluation of potential societal harms like bias, discrimination, and behavioral manipulation, as well as catastrophic risks such as loss of control and facilitated manufacture of WMDs. Critically, it should not authorize the deployment of an advanced AI system unless the developer can demonstrate it is ethical, fair, safe, and reliable, and that its potential benefits outweigh its risks.

We offer the following additional recommendations:

- A federal oversight body, similar to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, should be created to administer this AI licensing regime. Since AI is a moving target, pre- and post-deployment regulations should be designed with agility in mind.

- Given that AI harms are borderless, we need rules of the road with global buy-in. The U.S. should lead in intergovernmental standard-setting discussions. Events aimed at regulatory consensus-building, like the upcoming U.K. AI Safety Summit, must continue to bring both allies and adversaries to the negotiating table, with an eye toward binding international agreements. International efforts to manage AI risks must include the voices of all major AI players, including the U.S., U.K., E.U., and China, as well as countries that are not developing advanced AI but are nonetheless subject to its risks, including much of the Global South.

- Lawmakers must move towards a more participatory approach to AI policymaking that centers the voices of civil society, academia, and the public. Industry voices should not dominate the conversation, and a concerted effort should be made to platform a diverse range of voices so that the policies we craft today can serve everyone, not just the wealthiest few.

Encode Justice, a movement of nearly 900 young people worldwide, represents a generation that will inherit the AI reality we are currently building. In the face of one of the most significant threats to our generation’s shared future—the specter of catastrophic AI—we refuse to bury our heads in the sand. At the same time, we refuse to abandon our unfinished efforts to mitigate existing harms and create a more equal and just America. The Future of Life Institute remains committed to steering this transformative technology for the good of humanity, and the ongoing, out-of-control AI arms race risks our lives, our civil liberties, and our wellbeing. Together, we see an urgent moral imperative to confront present-day risks and future-proof for oncoming ones. AI licensing presents an opportunity to do both.

Sincerely,

AI Insight Forum: Innovation

October 24, 2023

Written Statement of Dr. Max Tegmark

Co-Founder and President of the Future of Life Institute

Professor of Physics at Massachusetts Institute of Technology

I first want to thank Majority Leader Schumer, the AI Caucus, and the rest of the Senators and staff who organized today’s event. I am grateful for the opportunity to speak with you all, and for your diligence in understanding and addressing this critical issue.

My name is Max Tegmark, and I am a Professor of Physics at MIT’s Institute for Artificial Intelligence and Fundamental Interactions and the Center for Brains, Minds and Machines. I am also the President and Co-Founder of the Future of Life Institute (FLI), an independent non-profit dedicated to realizing the benefits of emerging technologies and minimizing their potential for catastrophic harm.

Since 2014, FLI has worked closely with experts in government, industry, civil society, and academia to steer transformative technologies toward improving life through policy research, advocacy, grant-making, and educational outreach. In 2017, FLI coordinated development of the Asilomar AI Principles, one of the earliest and most influential frameworks for the governance of AI. FLI serves as the United Nations Secretary General’s designated civil society organization for recommendations on the governance of AI, and has been a leading voice in identifying principles for responsible development and use of AI for nearly a decade.

More recently, FLI made headlines by publishing an open letter calling for a six-month pause on the training of advanced AI systems more powerful than GPT-4, the state-of-the-art at the time of its publication. It was signed by more than 30,000 experts, researchers, industry figures, and other leaders, and sounded the alarm on ongoing, unchecked, and out-of-control AI development. As the Letter explained, the purpose of this pause was to allow our social and political institutions, our understanding of the capabilities and risks, and our tools for ensuring the systems are safe, to catch up as Big Tech companies continued to race ahead with the creation of increasingly powerful, and increasingly risky, systems. In other words, “powerful AI systems should be developed only once we are confident that their effects will be positive and their risks will be manageable.”

Innovation does not require uncontrollable AI

The call for a pause was widely reported, but many headlines missed a crucial nuance, a clarification in the subsequent paragraphs key to realizing the incredible promise of this transformative technology. The letter went on to read:

This does not mean a pause on AI development in general, merely a stepping back from the dangerous race to ever-larger unpredictable black-box models with emergent capabilities.

AI research and development should be refocused on making today’s powerful, state-of-the-art systems more accurate, safe, interpretable, transparent, robust, aligned, trustworthy, and loyal.

It is not my position, nor is it the position of FLI, that AI is inherently bad. AI promises remarkable benefits – advances in healthcare, new avenues for scientific discovery, increased productivity, among many more. What I am hoping to convey, however, is that we have no reason to believe vastly more complex, powerful, opaque, and uncontrollable systems are necessary to achieve these benefits. That innovation in AI, and reaping its untold benefits, does not have to mean the creation of dangerous and unpredictable systems that cannot be understood or proven safe, with the potential to cause immeasurable harm and even wipe out humanity.

AI can broadly be grouped into three categories:

- “Narrow” AI systems – AI systems that are designed and optimized to accomplish a specific task or to be used in a specific domain.

- Controllable general-purpose AI systems – AI systems that can be applied to a wide range of tasks, including some for which they were not specifically designed, with general proficiency up to or similar to the brightest human minds, and potentially exceeding the brightest human minds in some domains.

- Uncontrollable AI systems – Often referred to as “superintelligence,” these are AI systems that far exceed human capacity across virtually all cognitive tasks, and therefore by definition cannot be understood or effectively controlled by humans.

The first two categories have already yielded incredible advances in biochemistry, medicine, transportation, logistics, meteorology, and many other fields. There is nothing to suggest that these benefits have been exhausted. In fact, experts argue that with continued optimization, fine-tuning, research, and creative application, the current generation of AI systems can effectively accomplish nearly all of the benefits from AI we have thus far conceived, with several decades of accelerating growth. We do not need more powerful systems to reap these benefits.

Yet it is the stated goal of the leading AI companies to develop the third, most dangerous category of AI systems. A May 2023 blog post from OpenAI rightly points out that “it’s worth considering why we are building this technology at all.” In addition to some of the benefits mentioned above, the blog post justifies continued efforts to develop superintelligence by espousing that “it would be […] difficult to stop the creation of superintelligence” because “it’s inherently part of the technological path we are on.”

The executives of these companies have acknowledged that the risk of this could be catastrophic, with the legitimate potential to cause mass casualties and even human extinction. In a January 2023 interview, Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, said that “the bad case […] is, like, lights out for all of us.” In May 2023, Altman, along with Demis Hassabis, CEO of Google Deepmind, Dario Amodei, CEO of Anthropic, and more than 350 other executives, researchers, and engineers working on AI endorsed a statement asserting that “itigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority alongside other societal-scale risks such as pandemics and nuclear war.”

It is important to understand that creation of these systems is not inevitable, particularly before we can establish the societal, governmental, and technical mechanisms to prepare for and protect against their risks. The race toward creating these uncontrollable AI systems is the result of a tech sector market dynamic where prospective investment and perverse profit incentives drive reckless, runaway scaling to create the most powerful possible systems, at the expense of safety considerations. This is what “innovation” means to them.

But creating the most powerful system does not always mean creating the system that best serves the well-being of the American people. Even if we “win” the global race to develop these uncontrollable AI systems, we risk losing our social stability, security, and possibly even our species in the process. Far from ensuring geopolitical dominance, the destabilizing effect of haphazard proliferation of increasingly powerful AI systems is likely to put the United States at a substantial geopolitical disadvantage, sewing domestic discord, threatening national security, and harming quality of life. Our aspirations should instead be focused on innovation that improves our nation and our lives by ensuring that the systems we deploy are controllable, predictable, reliable, and safe – systems that do what we want them to, and do it well.

For a cautionary example, we can look to the emergence of recommender algorithms in social media. Over the past decade, tremendous strides were made in developing more effective algorithms for recommending content based on the behavior of users. Social media in general, and these algorithms in particular, promised to facilitate interpersonal connection, social discourse, and exposure to high-quality content.

Because these systems were so powerful and yet so poorly understood, however, society was not adequately equipped to protect against their potential harms. The prioritization of engagement in recommender systems led to an unforeseen preference for content evocative of negative emotion, extreme polarization, and the promotion of sensationalized and even fabricated “news,” fracturing public discourse and significantly harming mental and social health in the process. The technology was also weaponized against the American people by our adversaries, exacerbating these harms.

For uncontrollable AI systems, these types of misaligned preferences and unexpected ramifications are likely to be even more dangerous, unless adequate oversight and regulation are imposed. Much of my ongoing research at MIT seeks to advance our understanding of mechanistic interpretability, a field of study dedicated to understanding how and why these opaque systems behave the way they do. My talented students and colleagues have made incredible strides in this endeavor, but there is still much work to be done before we can reliably understand and predict the behavior of today’s most advanced AI systems, let alone potential systems that can operate far beyond human cognitive performance.

AI innovation depends on regulation and oversight

Though AI may be technically complex, Congress has extensive experience putting in place the necessary governance to mitigate risks from new technologies without foreclosing their benefits. In establishing the Federal Aviation Administration, you have facilitated convenient air travel, while ensuring that airplanes are safe and reliable. In establishing the Food and Drug Administration, you have cultivated the world’s leading pharmaceutical industry, treating ailments previously thought untreatable, while ensuring that the medicine we take is safe and will not cause undue harm.

The same can and should be done for AI. In order to harness the benefits of AI and minimize its risks, it is essential that we invest in further improving our understanding of how these systems work, and that we put in place the oversight and regulation necessary to ensure that if these systems are created and deployed, that they will be safe, ethical, reliable, and beneficial.

Regulation is often framed as an obstacle to innovation. But history has shown that failure to adequately regulate industries that pose catastrophic risk can be a far greater obstacle to technological progress. In 1979, the Three Mile Island nuclear reactor suffered a partial meltdown resulting from a mechanical failure, compounded by inadequate training and safety procedures among plant operators and management.

Had the nuclear energy industry been subject to sufficient oversight for quality assurance of materials, robust auditing for safe operating conditions, and required training standards for emergency response procedures, the crisis could likely have been avoided. In fact, subsequent investigations showed that engineers from Babcock & Wilcox, the developers of the defective mechanism, had identified the design issue that caused the meltdown prior to the event, but failed to notify customers.

The result of this disaster was a near-complete shuttering of the American nuclear energy industry. The catastrophe fueled ardent anti-nuclear sentiment among the general public, and encouraged reactionary measures that made development of new nuclear power plants costly and infeasible. Following the incident at Three Mile Island, no new nuclear power plants were authorized for construction in the United States for over 30 years, foreclosing an abundant source of clean energy, squandering a promising opportunity for American energy independence, and significantly hampering innovation in the nuclear sector.

We cannot afford to risk a similar outcome with AI. The promise is too great. By immediately implementing proactive, meaningful regulation of the AI industry, we can reduce the probability of a Three Mile Island-like catastrophe, and safeguard the future of American AI innovation.

Recommendations

To foster sustained innovation that improves our lives and strengthens our economy, the federal government should take urgent steps by enacting the following measures:

- Protect against catastrophes that could derail innovation, and ensure that powerful systems are developed and deployed only if they will safely benefit the general public. To do so, we must require that highly-capable general purpose AI systems, and narrow AI systems intended for use in high-risk applications such as critical infrastructure, receive independent audits and licensure before deployment. Importantly, the burden of proving suitability for deployment should fall on the developer of the system, and if such proof cannot be provided, the system should not be deployed. This means approval and licensure for development of uncontrollable AI should not be granted at all, at least until we can be absolutely certain that we have established sufficient protocols for training and deployment to keep these systems in check.

Auditing should include pre-training evaluation of safety and security protocols, and rigorous pre-deployment assessment of risk, reliability, and ethical considerations to ensure that the system does not present an undue risk to the well-being of individuals or society, and that the expected benefits of deployment outweigh the risks and harmful side effects. These assessments should include evaluation of potential risk from publishing the system’s model weights – an irreversible act that makes controlling the system and derivative systems virtually impossible – and provide requisite limitations on publication of and access to model weights as a condition of licensure. The process should also include continued monitoring and reporting of potential safety, security, and ethical concerns throughout the lifetime of the AI system. This will help identify and correct emerging and unforeseen risks, similar to the pharmacovigilance requirements imposed by the FDA. - Develop and mandate rigorous cybersecurity standards that must be met by developers of advanced AI to avoid the potential compromise of American intellectual property, and prevent the use of our most powerful systems against us. To enforce these standards, the federal government should also require registration when acquiring or leasing access to large amounts of computational hardware, as well as when conducting large training runs. This would facilitate monitoring of proliferation of these systems, and enhance preparedness to respond in the event of an incident.

- Establish a centralized federal authority responsible for monitoring, evaluating, and regulating general-purpose AI systems, and advising other agencies on activities related to AI within their respective jurisdictions. In many cases, existing regulatory frameworks may be sufficient, or require only minor adjustments, to be applicable to narrow AI systems within specific sectors (e.g. financial sector, healthcare, education, employment, etc.). Advanced general-purpose AI systems, on the other hand, cut across several jurisdictional domains, present unique risks and novel capabilities, and are not adequately addressed by existing, domain-specific regulations or authorities. The centralized body would increase the efficiency of regulating these systems, and help to coordinate responses in the event of an emergency caused by an AI system.

- Subject developers of advanced general-purpose AI systems (i.e. those with broad, unpredictable, and emergent capabilities) to liability for harms caused by their systems. This includes clarifying that Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act does not apply to content generated by AI systems, even if a third-party provided the prompt to generate that content. This would incentivize caution and responsibility in the design of advanced AI systems, aligning profit motives with the safety and security of the general public to further protect against catastrophes that could derail AI innovation.

- Increase federal funding for research and development into technical AI safety, reliable assessments and benchmarks for evaluating and quantifying risks from advanced AI systems, and countermeasures for identifying and mitigating harms that emerge from misuse, malicious use, or unforeseen behavior of advanced AI systems. This will allow our tools for assessing and enhancing the safety of systems to keep pace with advancements in the capabilities of those systems, and will present new opportunities for innovating systems better aligned with the public interest.

Innovation is what is best, not what is biggest

I have no doubt there is consensus among those participating in this Forum, whether from government, industry, civil society, or academia, that the best path forward for AI must foster innovation, that American ingenuity should not be stifled, and that the United States should continue to act as a leader in technological progress on the global stage. That’s the easy part.

The hard part is defining what exactly “innovation” means, and what type of leader we seek to be. To me, “innovation” means manifesting new ideas that make life better. When we talk about American Innovation, we are talking not just about the creation of new technology, but about how that technology helps to further democratic values and strengthen our social fabric. How it allows us to spend more time doing what we love with those we love, and keeps us safe and secure, both physically and financially.

Again, the nuance here is crucial. “Innovation” is not just the manifestation of new ideas, but also ensuring that the realization of those ideas drives us toward a positive future. This means that a future where America is a global leader in AI innovation does not necessarily mean that we have created a more powerful system — that is, a system with more raw power, that can do more things. What it means is that we have created the systems that lead to the best possible America. Systems that are provably safe and controllable, where the benefits outweigh the risks. This future is simply not possible without robust regulation of the AI industry.

Why do you care about AI Existential Safety?

I think there are real near-term AI risks. These range from bad to catastrophic. I don’t want to live in a world where the very technology we’ve created to make our lives easier and better ends up causing irreparable harm to humanity. But beyond the practical considerations, I care about AI existential safety because I care about the future of humanity. I believe that our species has the potential to achieve incredible things, but we are also vulnerable to making catastrophic mistakes. AI could be one of the most powerful tools we have to help us solve some of the biggest problems facing our world today, but only if we can ensure its safe and responsible development. Ultimately, I care about AI existential safety because I care about the well-being of all sentient beings. We have a responsibility to create a future that is both technologically advanced and morally just, and ensuring the safety of AI is a critical part of that mission.

Please give at least one example of your research interests related to AI existential safety:

One thing I’ve been concerned about is how undesirable traits can be selected for in a series of repeated games. There are classes of games which can potentially reinforce certain undesirable traits. For example, in repeated games where the players are in competition with each other, traits like spitefulness can be selected for if they prove advantageous. Spiteful behaviour involves intentionally harming others, even if it comes at a cost to oneself. In certain games, such behaviours can lead to gains and thus get reinforced. Another example is in social networks, where algorithms may prioritise content that is more likely to elicit strong emotional responses from users, such as anger or outrage. This can result in the reinforcement of negative and polarising views, leading to further division and conflict in society. The concern is that if AI systems are designed to optimise for certain outcomes without considering the broader impact on society, they may inadvertently reinforce undesirable traits or behaviours. This could have serious consequences, particularly in the case of autonomous systems where there is no human oversight.

Why do you care about AI Existential Safety?

There is a meaningful chance that AGI will be developed within the next 50 years. This will without doubt lead to transformative economic and societal change. There is no guarantee this transformation will be a positive one, and it could even lead to extinction of all life on Earth (or worse). As such, I believe the careful study of AGI safety is of fundamental importance for the future of humanity.

Please give at least one example of your research interests related to AI existential safety:

My focus is on RL safety, as I believe many of the greatest dangers of AGI arise due to the agentic nature of models trained in an RL setting. Previously, I worked on developing deep learning-based alternatives to RL (Howe et al., 2022) and on understanding the phenomenon of reward hacking in RL (Skalse et al., 2022). In the near future, I will be working on adversarial attacks and robustness of superhuman RL systems.

Why do you care about AI Existential Safety?

I believe that research in AI existential safety has a good chance of reducing the likelihood that transformative AI leads to large negative outcomes (e.g. due to catastrophic or existential risks or via locking in a great deal of suffering, especially but not limited to non-human animals).

I am especially concerned with questions of governance. Our window for governing transformative AI systems could be narrow if there is significant competitive pressure to build the most capable AI systems. Good governance of AI development can ensure that the field has the time and resources they need to invent and disseminate technical and societal solutions to long-term risks.

Please give at least one example of your research interests related to AI existential safety:

My research models how to best design policies for reducing risks from transformative AI. One example of my work is the following paper: Safe Transformative AI via a Windfall Clause (arxiv.org/abs/2108.09404): This paper extends a model of transformative AI competition with a Windfall Clause (see The Windfall Clause) to show how it is possible to design a Windfall Clause that overcomes two challenges: firms must have reason to join, and their commitments must be credible. The results suggest that firms benefit from joining a Windfall Clause under a wide range of scenarios. Hence, the paper provides evidence that the Windfall Clause may be an effective tool for reducing the risk from competition for transformative AI.

I am also a member of Modeling Cooperation. We recently built a web app which implements the Safety- Performance Tradeoff model created by Robert Trager, Paolo Bova, Nicholas Emery-Xu, Eoghan Stafford, and Allan Dafoe (spt.modelingcooperation.com). The web app allows other researchers and decision-makers to explore how improvements in technical AI safety could affect the safety choices of competing AI developers.

Why do you care about AI Existential Safety?

I have for a long time believed that the alignment problem would pose an existential risk if AGI was developed, but have been sceptical of non-trivial probabilities of that occuring. However, recently I have significantly increased my credence in short-term timelines due to AGI. This is partly because of the recent progress in LLMs. More significantly, it is because I have in my research found (to me) surprising overlap between the computational models we can use to explain human cognition, and those used to design artificial agents. This makes me think that we are approximating general principles of intelligence, and that AGI is realistic. Consequently, I want to do what I can to contribute to the mitigation of the alignment problem.

Please give at least one example of your research interests related to AI existential safety:

I am interested in understanding the structure of human values from an empirical standpoint so that an AGI could use this structure to generatively predict our preferences, even when we have failed to specify them, or have specified them incorrectly. A part of my current research project is to model this structure using reinforcement learning models. If that would work, then I believe it could provide a solution to a significant component of the alignment problem.

Why do you care about AI Existential Safety?

With the increasing capabilities of AI systems, it will become imperative to understand as well as ensure that these models behave in ways that are in accordance with human values and preferences. Such alignment, although possible to be achieved implicitly during learning, will most likely have to be injected via explicit mechanisms. If we fail to achieve such alignment, this can result in catastrophic outcomes, including existential risk for humanity.

Please give at least one example of your research interests related to AI existential safety:

- Empirical theory of deep learning i.e., trying to understand deep learning systems in a better way, before trying to maximize their performance

- Interpretability i.e., try to develop models that can explain their predictions in a faithful manner

- Develop systems that are more biologically plausible in order to better understand how such values can be hard-coded into the model directly, without asking them to learn it from data. Humans seem to have a moral compass that guides them independently of their world knowledge.

Why do you care about AI Existential Safety?

AI Existential Safety is extremly important because as AI systems become more advanced, they may be able to perform tasks that have significant consequences in the real world. If such systems are not designed and tested carefully, they could potentially cause harm or make mistakes that have serious consequences. By focusing on AI existential safety, we can help ensure that AI systems are beneficial to society and do not cause unintended harm. I have two clues, one practical, and the other philosophical.

1. My investigations on large language models had shown the possible dangerous feedbacks from these models without possible interpretations and the potential adoption of these models in real world systems could bring out the harmful results for humanity. To keep humanity sustainable, we should pay more attention to AI existential safety.

2. AI existential safety research also has many deep influence on our consideration of the future of humanity, the shape, development and the real meaning of existence, which are very interesting topics needing exploration through the intersecting perspectives of people with different backgrounds and culture.

Please give at least one example of your research interests related to AI existential safety:

I am working on ontological anti-crisis theory combining model theory, game theory and computational

complexity theory to give theoretical foundation for ontological crisis problem.

OAC theory put ontological crisis problem through a more theoretical view. I design the bounds and dynamics of the development of ontology for a model and made completeness and incompleteness results based on the construction which can be an analysis foundation for large models.

Some related constructions and design for OAC theory.

- onto Bounds

We consider bounds of ontology for specific task or problem:- upper bound of ontology for a task

- lower bound of ontology for a task

- onto Dynamics

- parallel ontology

- ontology intersecting

- one ontology absorbs another ontology

- ontology evolution

- meta ontology

- onto Actions

build / learn / reset / collapse

With solid mathematical foundations and deep results from TCS/Logic, more building blocks could emerge to help us dealing with ontological crisis problems and many other related AI existential safety problems, which is also a bridge for many researchers and students from different areas to work together for a better future with safe AI.

Why do you care about AI Existential Safety?

As a Human Factors practitioner, I have spent my career attempting to understand and optimise Human health and wellbeing in a broad set of domains. Since the work of Bainbridge on the ironies of automation, AI safety has formed a central component of my work. I am passionate about AI safety as, whilst I can see that AI could potentially revolutionise human health and wellbeing on a global scale, I am also keenly aware of the many risks and unwanted emergent properties that could arise. It is my firm belief that the key to managing these risks, some of which are existential, is the application of Human Factors theory, methods, and knowledge to support the design of safe, ethical, and usable AI. As such, a large component of my work to date has focused on AI safety, and my current research interests centre around the use of Human Factors to manage the risks associated with AI and AGI.

Please give at least one example of your research interests related to AI existential safety:

I am currently the chief investigator on an Australian Research Council funded Discovery project involving the application of sociotechnical systems theory and Human Factors methods to manage the risks associated with AGI. The research involves the application of prospective modelling techniques to identify the risks associated with 2 ‘envisioned world’ AGI systems, an uncrewed combat aerial vehicle system (The Executor) and a road transport management AGI (MILTON). Based on the risks identified we are currently developing recommendations for a suite of controls that are required to ensure that risks are effectively managed and that the benefits of AGI can be realised. The outputs of the research will provide designers, organisations, regulators and governments with the information required to support development and implementation of the controls needed to ensure that AGI systems operate safely and efficiently.

I am also the chief investigator on a Trusted Autonomous Systems funded program of work that involves the development of a Human Factors framework to support the design of safe, ethical, and usable AI in defence.

Why do you care about AI Existential Safety?

The high-level reasoning for why I care about AI x-safety is as follows.

- I care about humanity’s welfare and potential.

- AGI would likely be the most transformative technology ever developed.

- Intelligence has enabled human dominance of the planet.

- A being that possesses superior intelligence would likely outcompete humans if misaligned.

- Even if we aligned AGI, systemic risks might still result in catastrophe (e.g., conflict between AGIs)

- The ML research community is making rapid progress towards AGI, such that it appears likely to me that AGI will be achieved this century, if not in the next couple of decades.

- It seems unlikely that AGI would be aligned by default. It also seems to me we have no plan to deal with misuse or systemic risks from AGI.

- The ML research community is not currently making comparable progress on alignment.

- Progress on safety seems tractable.

- Technical alignment is a young field and there seems to be much low-hanging fruit.

- It seems feasible to convince the ML research community about the importance of safety.

- Coordination seems possible amongst major actors to positively influence the development of AGI.

Please give at least one example of your research interests related to AI existential safety:

My research mainly revolves around development alignment (e.g., cooperativeness, corrigibility) and capability (e.g., non-myopia, deception) evaluations of language models. The goal of my work is to develop both “warning shots” and threshold metrics. A “warning shot” would ideally alert important actors, such as policymakers, that coordination was immediately needed on AGI. A threshold metric would be something that key stakeholders would ideally agree upon, such that if a model exceeded the threshold (e.g., X amount of non-myopia), the model would not be deployed. I’ll motivate my work on evaluations of language models specifically in the following.

- It is likely that language models (LMs) or LM-based systems will constitute AGI in the near future.

- Language seems to be AI-complete.

- Language is extremely useful for getting things done in the world, such as by convincing people to do things, running programs, interacting with computers in arbitrary ways, etc.

- I think there is a > 30% chance we get AGI before 2035.

- I think there is a good chance that scaling is the main thing required for AGI, given the algorithmic improvements we can expect in the next decade.

- I partially defer to Ajeya’s bioanchors report.

- At a more intuitive level, the gap for text generative models between 2012 and now seems about as big as the gap between text generative models now and AGI. Increasing investments into model development makes me think we will close this gap, barring something catastrophic (e.g., nuclear war).

- No alignment solution looks on track for 2035.

- By an alignment solution, I mean something that gives us basically 100% probability (or a high enough probability such that we won’t expect an AI to turn on us for a very long time) that an AI will try to do what an overseer intends for them to do.

- An alignment solution will probably need major work into the conceptual foundations of goals and agency, which does not seem at all on track.

- Any other empirical solution, absent solid conceptual foundations, might not generalize to when we actually have an AGI (but people should still work on them just in case!).

- Given the above, it seems most feasible to me to develop evaluations that convince people of the dangers of models and of the difficulty of alignment. The idea is then that we collectively decide not to build or deploy certain systems before we conclusively establish whether alignment is solvable or not.

- We have been able to coordinate on dangerous technologies before, like nuclear weapons, bioweapons.

- Building up epistemic consensus around AGI risk seems also good for dealing with a post- AGI world, since alignment is not sufficient for safety. Misuse and systemic risks (like value lock-in, conflict) remain issues, so we probably eventually need some global, democratically accountable body to handle AGI usage.

Why do you care about AI Existential Safety?

The values of this community align with my research:

A long-standing goal of artificial intelligence (AI) is to build machines that intelligently augment humans across a variety of tasks. The deployment of such automated systems in ever more areas of societal life has had unforeseen ramifications pertaining to robustness, fairness, security, and privacy concerns that call for human oversight. It remains unclear how humans and machines should interact in ways that promote transparency and trustworthiness between them. Hence, there is a need for systems that make use of the best of both human and machine capabilities. My research agenda aims to build trustworthy systems for human- machine collaboration.

Please give at least one example of your research interests related to AI existential safety:

My doctoral research focused on the intersecting domain of causal inference and explainable AI—which given the increasing use of often intransparent (“blackbox”) ML models for consequential decision-making—is of rapidly- growing societal and legal importance. In particular, I consider the task of fostering trust in AI by enabling and facilitating algorithmic recourse, which aims to provide individuals with explanations and recommendations on how best (i.e., efficiently and ideally at low cost) to recover from unfavorable decisions made by an automated system. To address this task, my work is inspired by the philosophy of science and how explanations are sought and explained between human agents, and builds on the framework of causal modeling, which constitutes a principled and mathematically rigorous way to reason about the downstream effects of causal interventions. In this regard, I contributed novel formulations for the counterfactual explanation and consequential recommendation problems, and delivered open-source solutions built using tools from gradient-based and combinatorial optimization, probabilistic modeling, and formal verification.

Why do you care about AI Existential Safety?

Ensuring the safety of AI models is currently one of the most crucial and, at the same time, important requirements. While AI remains one of the most promising technologies of the future, the potential risks are worrying and limit its adoption to strictly controlled environments. As a researcher, I feel the responsibility to direct our efforts to prevent catastrophic situations from happening. We are the ones primarily responsible for the AI we create. We will not have an out-of-control AI if we all together set up guidelines to be able to avoid it.

Please give at least one example of your research interests related to AI existential safety:

The primary focus of my research is on AI models and on the assessment and the improvement of their reliability. During my PhD, this topic has been addressed comprehensively at very different abstraction levels and from different perspectives. A key contribution of my research activities is the proposals of different fault injection tools and methodologies to easy and support the reliability assessment process. Next, relying on these analysis and results, strategies to detect and mitigate the effect of faults have been proposed. Nowadays, understanding how to reliably deploy AI models on safety-critical systems starts to be crucial. Indeed, my research findings show that artificial neural networks, although they are mimics of the human brain, cannot be considered inherently resilient. Their safety must be evaluated, preferably in conjunction with the hardware running the AI model. To raise the safety of AI models, a starting point might be to explain the behaviour of such predictive models: to comply with safety standards it is crucial to understand the reasons behind their choices, and to move beyond the black box view of artificial neural networks.

Tim is a policy researcher at the Future of Life Institute, where he contributes to multiple policy projects and leads FLI’s engagement on the development of European standards for artificial intelligence. Tim holds bachelor’s degrees in Data Science and Philosophy from the University of Marburg, as well as a master’s degree in Machine Learning from the University of Tübingen. Prior to joining FLI, Tim worked as a consultant for data science & AI at d-fine.

Alexandra Tsalidis joined FLI’s Policy team as part of a six-month fellowship through the Training for Good program. Her research focuses on analysing European AI policies and their effectiveness in mitigating AI risks. Previously, Alexandra worked as an affiliated researcher in the Ethical Intelligence Lab at Harvard Business School and a research assistant at the Shen Lab in Harvard’s Center for Bioethics. She holds a Master in Bioethics from Harvard Medical School and a BA in Law from the University of Cambridge.