United Nations Adopts Ban on Nuclear Weapons

Contents

Today, 72 years after their invention, states at the United Nations formally adopted a treaty which categorically prohibits nuclear weapons.

With 122 votes in favor, one vote against, and one country abstaining, the “Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons” was adopted Friday morning and will open for signature by states at the United Nations in New York on September 20, 2017. Civil society organizations and more than 140 states have participated throughout negotiations.

On adoption of the treaty, ICAN Executive Director Beatrice Fihn said:

“We hope that today marks the beginning of the end of the nuclear age. It is beyond question that nuclear weapons violate the laws of war and pose a clear danger to global security. No one believes that indiscriminately killing millions of civilians is acceptable – no matter the circumstance – yet that is what nuclear weapons are designed to do.”

In a public statement, Former Secretary of Defense William Perry said:

“The new UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons is an important step towards delegitimizing nuclear war as an acceptable risk of modern civilization. Though the treaty will not have the power to eliminate existing nuclear weapons, it provides a vision of a safer world, one that will require great purpose, persistence, and patience to make a reality. Nuclear catastrophe is one of the greatest existential threats facing society today, and we must dream in equal measure in order to imagine a world without these terrible weapons.”

Until now, nuclear weapons were the only weapons of mass destruction without a prohibition treaty, despite the widespread and catastrophic humanitarian consequences of their intentional or accidental detonation. Biological weapons were banned in 1972 and chemical weapons in 1992.

This treaty is a clear indication that the majority of the world no longer accepts nuclear weapons and does not consider them legitimate tools of war. The repeated objection and boycott of the negotiations by many nuclear-weapon states demonstrates that this treaty has the potential to significantly impact their behavior and stature. As has been true with previous weapon prohibition treaties, changing international norms leads to concrete changes in policies and behaviors, even in states not party to the treaty.

“This is a triumph for global democracy, where the pro-nuclear coalition of Putin, Trump and Kim Jong-Un were outvoted by the majority of Earth’s countries and citizens,” said MIT Professor and FLI President Max Tegmark.

“The strenuous and repeated objections of nuclear armed states is an admission that this treaty will have a real and lasting impact,” Fihn said.

The treaty also creates obligations to support the victims of nuclear weapons use (Hibakusha) and testing and to remediate the environmental damage caused by nuclear weapons.

From the beginning, the effort to ban nuclear weapons has benefited from the broad support of international humanitarian, environmental, nonproliferation, and disarmament organizations in more than 100 states. Significant political and grassroots organizing has taken place around the world, and many thousands have signed petitions, joined protests, contacted representatives, and pressured governments.

“The UN treaty places a strong moral imperative against possessing nuclear weapons and gives a voice to some 130 non-nuclear weapons states who are equally affected by the existential risk of nuclear weapons. … My hope is that this treaty will mark a sea change towards global support for the abolition of nuclear weapons. This global threat requires unified global action,” said Perry.

Fihn added, “Today the international community rejected nuclear weapons and made it clear they are unacceptable.It is time for leaders around the world to match their values and words with action by signing and ratifying this treaty as a first step towards eliminating nuclear weapons.”

Images courtesy of ICAN.

WHAT THE TREATY DOES

Comprehensively bans nuclear weapons and related activity. It will be illegal for parties to undertake any activities related to nuclear weapons. It bans the use, development, testing, production, manufacturing, acquiring, possession, stockpiling, transferring, receiving, threatening to use, stationing, installation, or deploying of nuclear weapons.

Bans any assistance with prohibited acts. The treaty bans assistance with prohibited acts, and should be interpreted as prohibiting states from engaging in military preparations and planning to use nuclear weapons, financing their development and manufacture, or permitting the transit of them through territorial waters or airspace.

Creates a path for nuclear states which join to eliminate weapons, stockpiles, and programs. It requires states with nuclear weapons that join the treaty to remove them from operational status and destroy them and their programs, all according to plans they would submit for approval. It also requires states which have other country’s weapons on their territory to have them removed.

Verifies and safeguards that states meet their obligations. The treaty requires a verifiable, time-bound, transparent, and irreversible destruction of nuclear weapons and programs and requires the maintenance and/or implementation of international safeguards agreements. The treaty permits safeguards to become stronger over time and prohibits weakening of the safeguard regime.

Requires victim and international assistance and environmental remediation. The treaty requires states to assist victims of nuclear weapons use and testing, and requires environmental remediation of contaminated areas. The treaty also obliges states to provide international assistance to support the implementation of the treaty. The text requires states to join the Treaty, and to encourage others to join, as well as to meet regularly to review progress.

NEXT STEPS

Opening for signature. The treaty will be open for signature on 20 September at the United Nations in New York.

Entry into force. Fifty states are required to ratify the treaty for it to enter into force. At a national level, the process of ratification varies, but usually requires parliamentary approval and the development of national legislation to turn prohibitions into national legislation. This process is also an opportunity to elaborate additional measures, such as prohibiting the financing of nuclear weapons.

First meeting of States Parties. The first Meeting of States Parties will take place within a year after the entry into force of the Convention.

SIGNIFICANCE AND IMPACT OF THE TREATY

Delegitimizes nuclear weapons. This treaty is a clear indication that the majority of the world no longer accepts nuclear weapons and do not consider them legitimate weapons, creating the foundation of a new norm of international behaviour.

Changes party and non-party behaviour. As has been true with previous weapon prohibition treaties, changing international norms leads to concrete changes in policies and behaviours, even in states not party to the treaty. This is true for treaties ranging from those banning cluster munitions and land mines to the Convention on the law of the sea. The prohibition on assistance will play a significant role in changing behaviour given the impact it may have on financing and military planning and preparation for their use.

Completes the prohibitions on weapons of mass destruction. The treaty completes work begun in the 1970s, when Chemical weapons were banned, and the 1990s when biological weapons were banned.

Strengthens International Humanitarian Law (“Laws of War”). Nuclear weapons are intended to kill millions of civilians – non-combatants – a gross violation of International Humanitarian Law. Few would argue that the mass slaughter of civilians is acceptable and there is no way to use a nuclear weapon in line with international law. The treaty strengthens these bodies of law and norm.

Remove the prestige associated with proliferation. Countries often seek nuclear weapons for the prestige of being seen as part of an important club. By more clearly making nuclear weapons an object of scorn rather than achievement, their spread can be deterred.

FLI sought to increase support for the negotiations from the scientific community this year. We organized an open letter signed by over 3700 scientists in 100 countries, including 30 Nobel Laureates. You can see the letter here and the video we presented recently at the UN here.

This post is a modified version of the press release provided by the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN).

About the Future of Life Institute

The Future of Life Institute (FLI) is a global think tank with a team of 20+ full-time staff operating across the US and Europe. FLI has been working to steer the development of transformative technologies towards benefitting life and away from extreme large-scale risks since its founding in 2014. Find out more about our mission or explore our work.

Related content

Other posts about FLI projects, Nuclear, Recent News

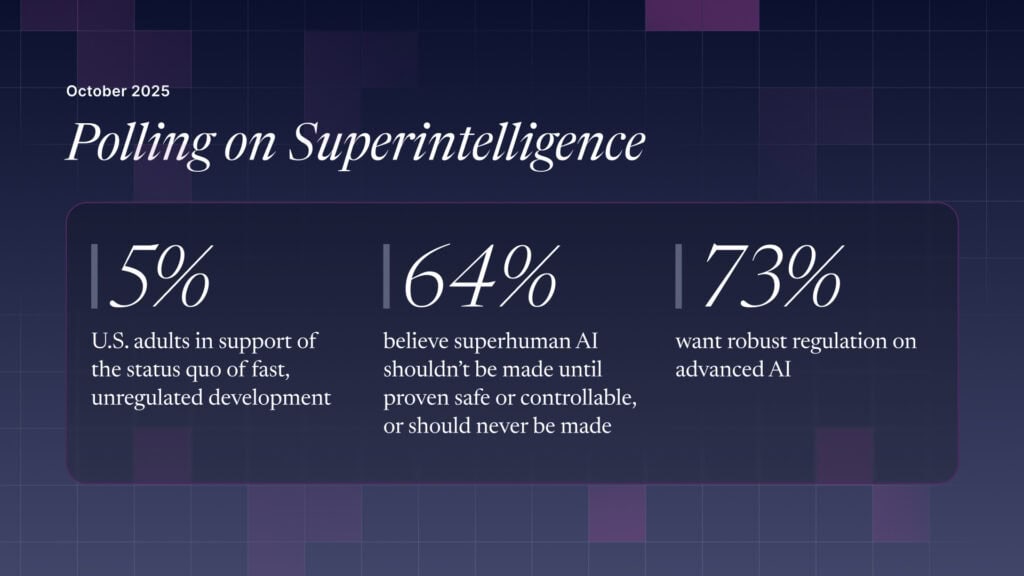

The U.S. Public Wants Regulation (or Prohibition) of Expert‑Level and Superhuman AI

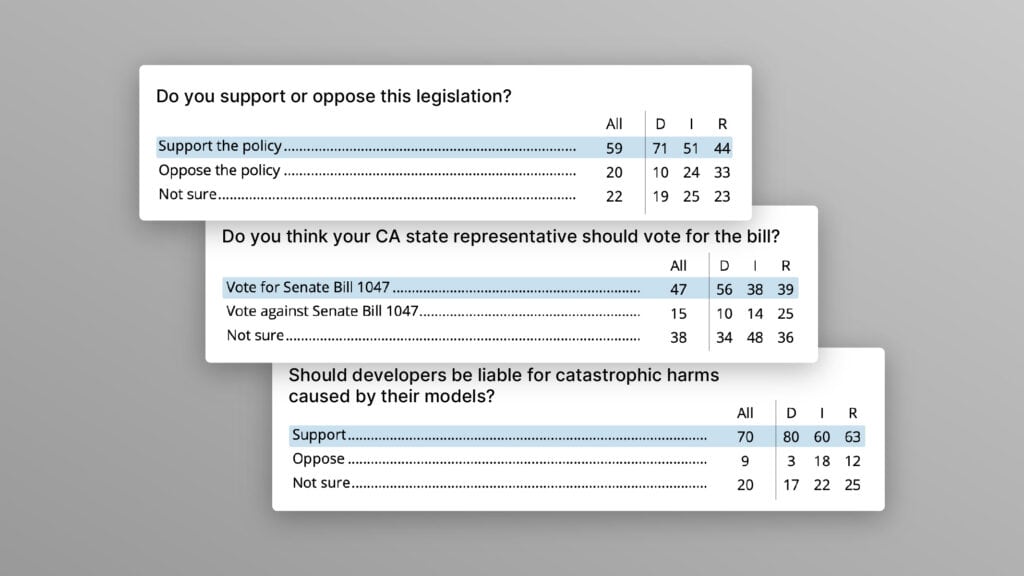

Poll Shows Broad Popularity of CA SB1047 to Regulate AI